Most North Carolinians realize that there are two agencies that deal with fishing in our state’s waters. One, the Wildlife Resources Commission (WRC), regulates hunting and freshwater fishing (Inland waters), while the other, the Marine Fisheries Commission (MFC) sets restrictions on fishing in salt and brackish waters (Coastal waters). These agencies have divided their respective responsibilities for decades. However, most North Carolinians probably do not realize that the WRC has recently proposed new rules that will significantly change the measures put in place by the state to protect fisheries habitat and dramatically restrict the opportunity of commercial fishermen to harvest fish in waters currently designated as coastal.

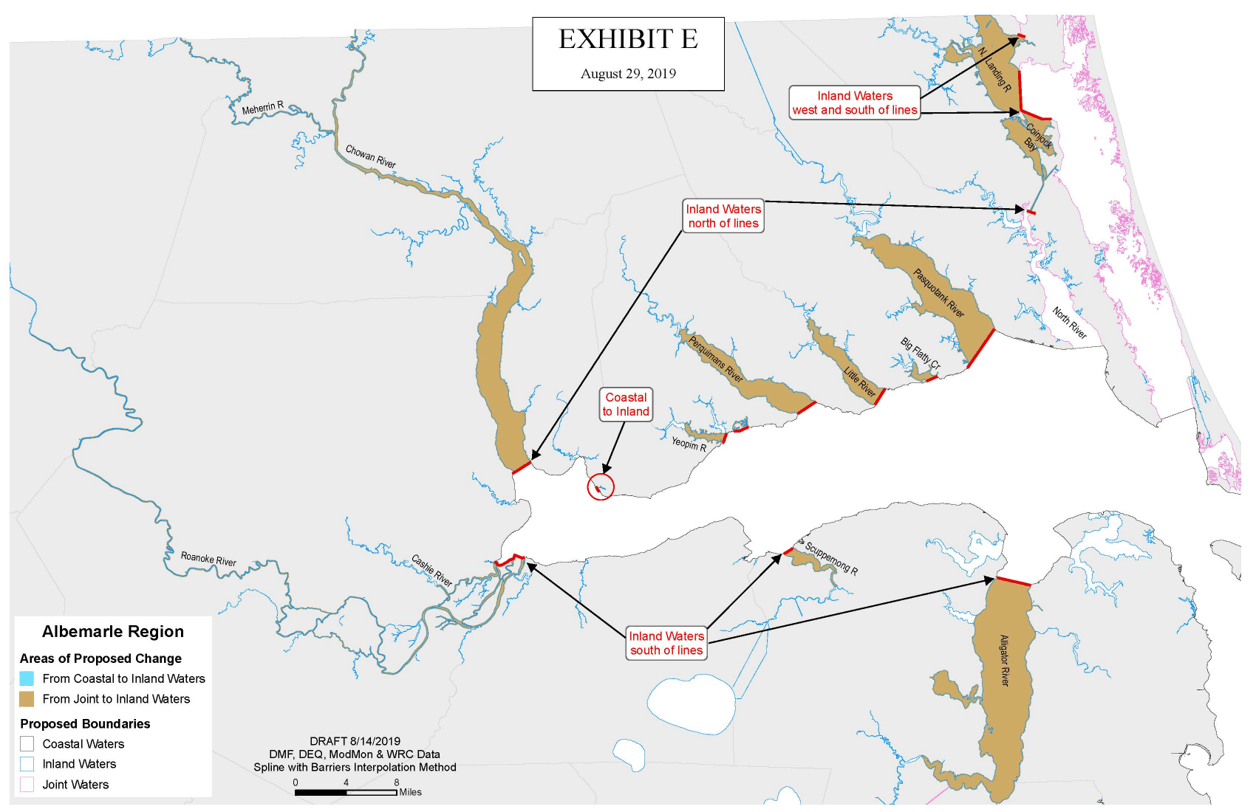

In August 2019 the WRC voted to proceed forward with formal rules that would substantially change boundaries between Coastal and Inland waters that have been in place for over 50 years. The WRC relied on a salinity value (salt concentration in the water) of 2.6 parts per thousand (ppt) (freshwater by definition usually has 0.0ppt salinity). Using such standards would greatly expand the fishing waters controlled by the WRC. The action proposed and voted on by the WRC causes major economic, environmental, administrative, legal and scientific concerns.

First, the proposed expansion of Inland waters will have negative economic impact. Commercial fishermen are prohibited from using crab pots to catch and sell blue crabs from Inland waters. Fishermen and scientists recognize that male blue crabs (jimmies) prefer lower salinity waters and grow to larger sizes in those waters. The blue crab fishery is North Carolina’s most important commercial fishery. Much of the current coastal waters being proposed to be reset as Inland waters include large portions of Albemarle Sound’s tributaries and these areas have been traditionally used by crab fishermen for years. Albemarle Sound is one of the top blue crab producing areas in North Carolina.

The proposed expansion of Inland waters will have another negative economic impact in the coastal region. Fishermen are prohibited from using gill nets to take and sell finfish in Inland waters. Fish such as striped mullet, catfish (various species), and white perch spend much of their lives in the lower salinity areas of our rivers and sounds and support economically important gill net fisheries. Albemarle Sound and its tributaries are important areas for these fisheries and have been utilized for decades by fishermen to provide fish, as well as other waters, to consumers.

Second, the General Assembly, which created the two agencies, passed laws that require the WRC and MFC to agree on where the boundaries for inland and coastal waters are. The MFC has NOT agreed to the proposed new boundaries. In fact, the agency that provides scientific data to the MFC on fisheries conservation, the NC Division of Marine Fisheries, has serious concerns about the WRC’s proposed changes. The proposed rule, if passed by the WRC, possibly violates the General Assembly’s laws, since the MFC has not concurred with the boundaries and the WRC decided to proceed with rulemaking procedures without having MFC agreement. The Chief Deputy Secretary of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), the lead stewardship agency in the Governor’s administration for the protection of North Carolina’s environmental resources, expressed concern that the WRC moved forward with the proposed boundaries with “little direct notice to the MFC or to DEQ”, further complicating the matter.

Third, and perhaps of concern to most North Carolinians is that the proposal boundary changes would remove waters critical to the state’s coastal fisheries from protection under coastal management, water quality and habitat conservation programs in North Carolina. These concerns are so substantial that the NC Coastal Resources Commission (CRC), who the General Assembly has empowered to protect fisheries habitat (such as Primary Nursery Areas), and manages coastal areas through the Coastal Area Management Act, has objected to the proposed boundary changes by the WRC. The CRC even took the extraordinary step to write the North Carolina Governor to express their concerns and opposition to the WRC’s actions.

The Deputy Secretary of NCDEQ also conveyed concerns to the WRC that the proposed changes will likely degrade North Carolina water quality in the coastal area due to removing stormwater runoff protection measures. Stormwater runoff is known to contribute heavily to increases in fecal coliform levels, which impact use of waters for recreation. Stormwater protection measures are tied to existing uses of the waters, such as commercial fishing, and also to CRC designations as Areas of Environmental Concern. If Coastal waters are reclassified as Inland waters, those protections could be jeopardized.

Fourth, several years ago our legislative leaders passed the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) and passed regulatory reform measures to “improve and streamline the regulatory process to stimulate job creation, to eliminate unnecessary regulation…” As part of the Act and other regulatory reform steps, rule-making agencies such as the MFC and WRC must review rules at least once every 10 years. If a rule is not reviewed it will expire. The APA and regulatory reform statutes requires the rules to be reviewed by a separate Rules Commission and by a Legislative Review Committee before it can go in effect again to examine redundancy and economic impacts.

The boundaries of Inland and Coastal waters are ONLY found in the MFC rulebook. The WRC references the MFC rules for their listings and incorporates the specific descriptions of boundaries by referencing the MFC rule. The two government agencies have essentially the same rules to describe their respective geographical jurisdictions, just using different administrative references. The MFC completed their statutory required 10-year review of the set of rules involving Coastal/Inland waters boundaries in 2018. The MFC classified the boundary and jurisdiction rule set as necessary without substantive public interest and decided they should remain in effect unchanged. The Rules Commission and Legislative Review Committee approved the MFC’s rule-making reports as required by law.

In 2019 the WRC claimed that they must undertake a review and substantive modification of their Inland/Coastal boundary rules to comply with the required 10-year review of the APA and that the rules needed to be part of their 2020 rule cycle to meet the legislatively-mandated time line. This determination was made even though the MFC had completed their review of the set of boundary/jurisdiction rules in 2018, no comments were provided by the WRC during the MFC rule review and no public comment had been received under the MFC review process.

A major issue for the public and our legislative leaders is that two state agencies required to operate under the APA, passed as part of regulatory reform by our elected officials, have followed two disparate actions on essentially the same rules. The APA specifically states in subsection d) “Each agency shall determine whether its policies and programs overlap with the policies and programs of another agency. In the event two or more agencies’ policies and programs overlap, the agencies shall coordinate the rules adopted by each agency to avoid unnecessary, unduly burdensome, or inconsistent rules.” Clearly the intent of the APA was not followed and the APA was possibly violated by the WRC action.

A fifth major issue is that a level of 2.6ppt salinity used by the WRC does not reflect the most generally accepted scientific standards for definitions of estuaries (part of coastal waters) and appears to conflict with laws passed by the General Assembly. Our legislature has defined coastal fishing waters (under the MFC jurisdiction) as “the Atlantic Ocean; various coastal sounds; and estuarine waters up to the dividing line between coastal and inland waters as agreed upon by the WRC/MFC.” Most scientific definitions state estuaries are semi-enclosed water bodies where fresh and salt water mix and eventually open to the sea; most also state that they contain brackish waters, which are usually classified as those waters with salinities greater than 0.5ppt salinity. Most scientists agree that even waters with 0ppt salinity, but are influenced by lunar tides are considered estuarine waters.

Using a standard of 2.6ppt salinity would remove substantial proportions of estuarine waters from the MFC and transfer such waters to the WRC. The General Assembly has clearly stated in G.S. 113-132 and other laws that the MFC has jurisdiction over the conservation of marine and estuarine resources in NC, not the WRC. The proposed action by the WRC appears to violate the intent of our legislative leaders.

The WRC have stated that using an absolute 2.6 ppt salinity standard is an objective science-based approach for determining boundaries where freshwater fish are most abundant. There are other scientifically based and perhaps more appropriate, indicators that could be used if state agencies desired to modify the boundaries between Inland/Coastal fishing waters. In joint meetings with the WRC/MFC, the Division of Marine Fisheries suggested several other techniques. Fish species composition within various salinity ranges, fisheries characterization studies, salinity change rates or variations and lower salinity values that better reflect scientific literature are a few of the techniques that could be used.

Another issue in using the 2.6ppt absolute value in salinity to characterize fresh/coastal waters’ boundaries is that the value was based on studies performed in Chesapeake Bay. All objective scientists recognize substantial differences exist between Chesapeake Bay and the Albemarle/Pamlico Sound estuaries, where most of the proposed boundary changes are being suggested. One of the major differences is that Chesapeake Bay is tidally driven, experiencing two high and two low lunar tides per day. The Bay, with its large opening to the Atlantic Ocean and deep channels, is characterized by saltwater (coastal water) being driven much further into the estuaries. North Carolina has a unique barrier to the ocean, known as the Outer Banks, which substantially buffers much of our coastal waters from daily tidal influence. Pamlico/Albemarle Sounds are more heavily influenced by wind moving coastal (brackish) waters into inland (freshwater) areas and water flow from upstream sources.

It is clear and true that the WRC proposal to change the boundaries of Coastal/Inland waters using a 2.6ppt salinity value leads to significant environmental, economic, scientific, legal, and administrative issues. Citizens and leaders of North Carolina should be concerned about this proposal. The concerns are so substantial that they led the Deputy Secretary of NCDEQ, the leading environmental agency in North Carolina government, to state that the WRC’s proposal’s “consequences to the environment are simply not acceptable.” His statements could not be clearer or more concise. Let’s hope our Governor, who has the authority to address the action by the WRC, and our General Assembly members also agree.

Jess Hawkins has a Master of Science in Biology. He was a former Chief of Fisheries Management with the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries. He is currently an instructor with the Duke Marine Laboratory and North Carolina State University CMAST Laboratory teaching Marine Fisheries Ecology

Related Articles

The Saga of Southern Flounder

Related Articles Stay Up to Date With The Latest News & Updates Join Our Newsletter

The Saga of Southern Flounder; The Rest of the Story…

Related Articles Stay Up to Date With The Latest News & Updates Join Our Newsletter

Southern Flounder, by the Numbers

Related Articles Stay Up to Date With The Latest News & Updates Join Our Newsletter